Traditionally, it was thought that if you wanted to boost the economy, the central bank would reduce its interest rates. Normally, the rates offered on savings accounts would follow, and people would choose to spend more, and save less.

But there’s a limit, what economists called the “zero lower bound”. Cut rates too deeply, and savers would end up facing negative returns. In that case, this could encourage people to take their savings out of the bank and hoard them in cash. This could slow, rather than boost, the economy.

What is happening now should not – according to conventional thinking – be possible.

As central bank rates have turned negative, the rates offered on bank deposits have followed. Yet rather than stuffing cash under mattresses, people have left their money in the bank or spent it.

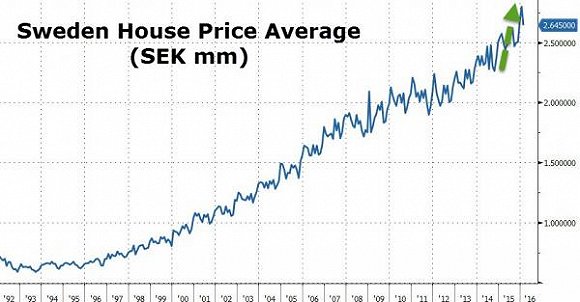

Nowhere is the experiment with negative rates more obvious than among Nordic central banks. Sweden – the first to dabble with negative rates – is perhaps the prime candidate for such experimentation.

The country already has high savings rates, the third highest in the developed world according to the OECDand, despite growing at healthy rates, there appears to be plenty of slack left in the economy to prevent an overheat.

Unemployment is unusually high for an advanced economy at more than 7pc, still well above its pre-crisis levels of sub-6pc. Crucially, the Riksbank’s mandate suggests that such a radical experiment is necessary. Policymakers have battled with deflation since late 2012, and with inflation at minus 0.2pc in August, it remains well below the central bank’s 2pc target.

To a great extent, the Riksbank’s hand has been forced by the plight of the eurozone. A tepid recovery in the currency union has required the European Central Bank (ECB) to bring in ever-looser policy.

As the ECB’s actions have weakened the euro against Sweden’s krona, the cost of importing goods into Sweden has fallen, and weighed down on inflation. The Riksbank has had to cut its own rates in response in an attempt to avoid deep deflation.

Sweden’s flexible approach to monetary policy has won it the plaudits of leading credit ratings agency. Standard and Poor’s recently reaffirmed the country’s triple AAA sovereign rating, remarking on the benefits it derives from “ample monetary policy flexibility”.

Noting that the Riksbank had introduced both negative interest rates and quantitative easing, S&P said that “should inflation rates stay low or the krona appreciate materially, the central bank could lower the repo rate further”.

Many City analysts believe that the Riksbank will continue cutting, reducing its key interest rate to minus 0.5pc by the end of the year. Switzerland’s is already deeper still, at minus 0.75pc, while Denmark and the eurozone have joined them as members of the negative zone.

What was once thought impossible now seems something that could come to the UK in the years to come. And even in the US, which is thought to be just months away from an interest rate rise, the idea of negative interest rates has gained attention.

At the most recent meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which decides US interest rates, one unnamed member said that they expected negative policy rates at the end of this year and next.

But can policymakers keep at this forever? Even if turns out that the lower bound was not negative, economists still believe that one exists.

Attempts to estimate the unknown vary, but the fees charged by credit companies give some indication as to how strongly we prefer to use cash. These can be as low as minus 3pc according to Barclays, indicating that central bankers have much more room to slash rates.

Pension funds might be among the first to abandon banks if things get too painful, because of what in effect can look like a tax on holding money.

One solution is to give savers nowhere else to go. This idea was floated by the Bank of England’s chief economist in recent weeks, who made the case that sub-zero rates will be needed in the near future.

Andy Haldane, a member of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), the UK’s equivalent of the FOMC suggested that to achieve properly negative rates, the abolition of cash itself might be necessary.

This is one reason why negative rates have been used in Nordic economies, where societies are already close to cashless. Even sellers of Sweden’s version of the Big Issue magazine - Situation Stockholm - are able to accept payment via debit or credit card.

For the immediate future, the British obsession with cash appears to be intensifying. The Bank of England has said that demand for banknotes and coins outstrips total spending in the economy.

Some of like to hoard it for peace of mind, while many of us hold it for day to day transactions. And much of it is held abroad, often in bureaux de change.

There are other - perhaps more sinister - motives to prefer non-electronic money. Unlike the money stored on spreadsheets, cash is almost completely untraceable. For those who value their privacy, or who deal in prohibited goods and services, there’s no beating it.

Last week, Charles Goodhart, a former MPC member, said that Swiss and ECB central bankers had been “absolutely shameless” in continuing to issue high denomination notes, printing 1,000 Swiss franc and 500 euro bills.

These high face values notes “are there to finance the drug deals”, Mr Goodhart said at the annual Money, Macro and Finance Conference in London. Sir Charles Bean, also a former deputy governor at the Bank of England, echoed Mr Goodhart’s concerns.

He said that was “all in favour of getting rid of big-denomination notes, which are used in the black economy”. Such a move could increase the cost of holding cash, pushing the lower bound on policy rates even lower. Sushil Wadhwani, a former MPC member, said: “We should make it much more expensive to hold cash.”

No politician is likely to prohibit cash entirely, at least not until it has already all but disappeared from day to day life. Concerns about surveillance and the power of the state are likely to grow, as electronic money is completely traceable.

“Cash is useful for small transactions, and until it disappears naturally, I would be loathe to say let’s outlaw it,” says Sir Charles.

但日本负利率后,楼市反而下跌啊!专"加"怎么解啊!